Every Automated System Is a Control System

Every Automated System Is a Control System

A distribution warehouse automated its loading dock safety system in 2021. Smart control panels coordinated hydraulic dock levelers, truck restraints, overhead doors, and inflatable seals. The sequence was critical: restrain the truck, extend the leveler, inflate the seal, then allow the door to open. Get the order wrong and you risk crushing equipment, damaging trailers, or creating a fall hazard for forklift operators.

The system worked flawlessly for eighteen months. Then one Tuesday morning, Bay 7 locked out. The operator pressed the button sequence. Nothing. The panel showed conflicting states—door closed, but also a fault. Leveler down, but restraint active. The display flickered between valid states too quickly to read.

The truck sat in the bay. The operator called maintenance. Maintenance called the panel vendor. No one could see what the system was seeing. No logs. No remote access. No diagnostic mode that didn't require physically opening the panel and connecting a laptop—which no one on-site knew how to do safely while the system was energized.

Four hours later, a technician traced the problem: a door interlock sensor with a loose connection. Instead of a clean on/off signal, it was chattering—sending intermittent pulses that the control logic interpreted as rapid state changes. The safety system, doing exactly what it was designed to do, refused to proceed because the door state was ambiguous.

The fix took ten minutes once diagnosed. The diagnosis took four hours and $800 in emergency service fees. The lost productivity cost more than that.

The system worked exactly as designed. It just had no way to tell anyone what it was experiencing.

Automation is often described as a way to remove humans from the loop. That framing is comforting—and wrong.

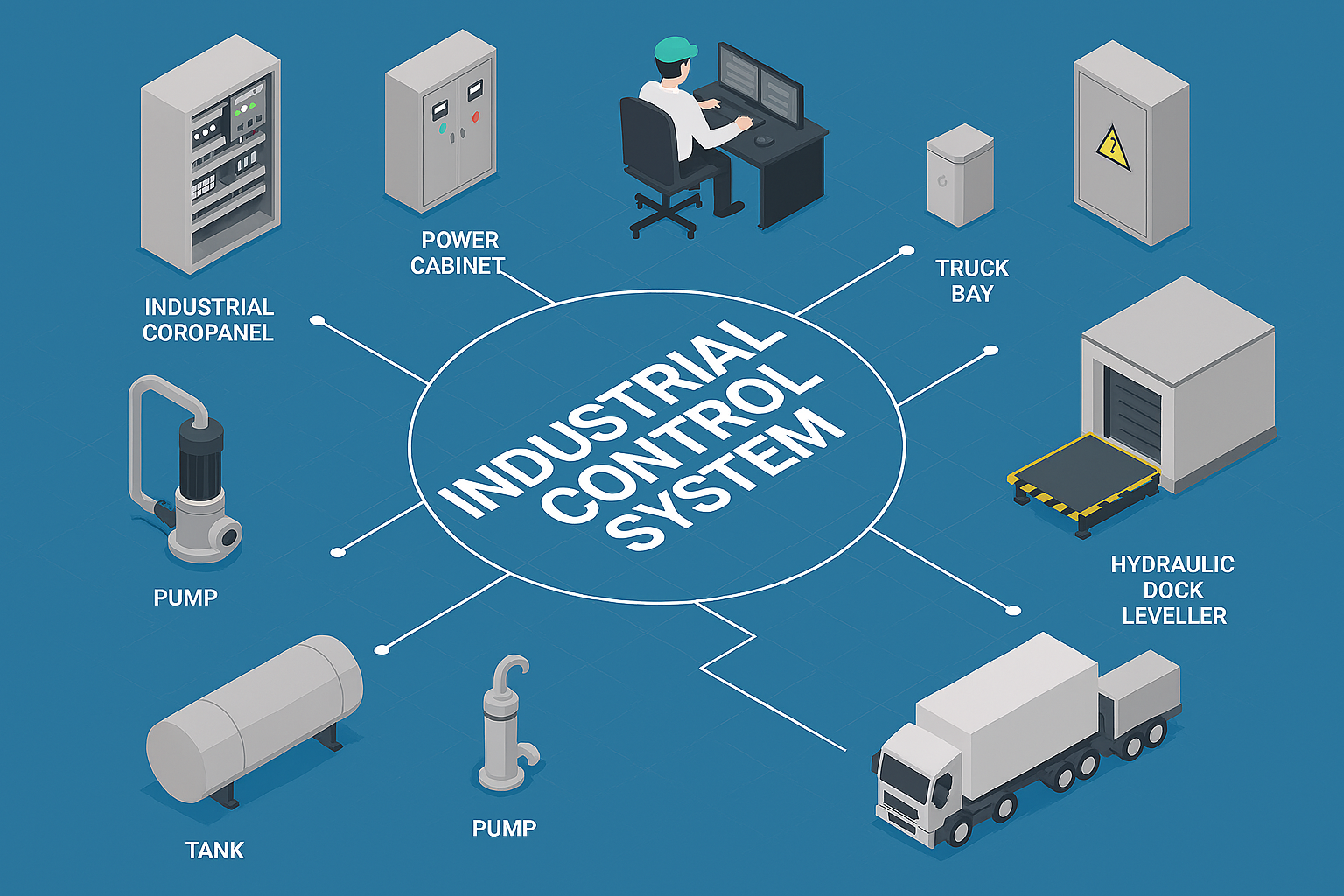

Automation does not eliminate control. It implements it. Every automated system is, at its core, a control system: something observes a process, compares it to intent, and acts to reduce the difference.

Whether that system lives in a PLC, a microcontroller, a cloud service, or an organization chart does not change the physics involved. Feedback, delay, noise, saturation, and stability still apply.

Ignoring that reality is how automated systems quietly become dangerous.

Automation Is Control With Commitment

In industrial environments, automation is not an abstraction. It closes a loop around something physical.

A valve moves. A motor spins. A door opens. A restraint engages. A process heats, cools, fills, or drains.

Once automated, those actions happen faster than human reaction time and with more consistency than human judgment. That is the point.

But it also means the consequences of design decisions arrive faster—and with less opportunity for intervention.

A human operator running a system manually makes continuous micro-adjustments based on observation, intuition, and context that never makes it into documentation. They notice when a sensor "feels sticky." They remember that the interlock on Bay 3 takes an extra half-second to settle. They know to wait for the hydraulic pump to stabilize before cycling again.

Automation doesn't have intuition. It has the logic you gave it and the sensors you installed. It will faithfully execute that logic with those sensors, even when the result is obviously wrong to anyone watching.

This is not a limitation of automation. It is the nature of it.

Automation is control with commitment. Once the loop is closed, the system will do exactly what you encoded—no more, no less—long after you've stopped paying attention. It won't second-guess itself. It won't notice that something feels off. It will enforce whatever rules you programmed, even when those rules produce unexpected behavior.

That dock control panel didn't know the door sensor was chattering. It knew the door state was changing rapidly, which violated the safety interlock logic. So it did exactly what it was supposed to: refuse to proceed. The fact that the state changes were caused by a failing sensor rather than an actual unsafe condition was invisible to the control logic.

The system couldn't distinguish between "door rapidly opening and closing" (dangerous, must prevent) and "door sensor failing" (annoying, should flag). Both looked the same from inside the control loop.

The Control Loop Is the Unit of Truth

It's tempting to talk about systems in terms of components: sensors, PLCs, networks, SCADA, cloud dashboards, HMI panels.

But components don't fail in isolation. Loops do.

A control loop tells you:

- What the system believes about the world

- How often it updates that belief

- How aggressively it responds

- What happens when measurements are missing or wrong

- What it does when it reaches its limits

If you want to understand an automated system, you don't start with the hardware list. You start by asking: where are the loops, and where aren't they?

That dock safety system had all the right components. The sensors were rated for the environment. The control panel had proper safety logic. The interlocks were correctly wired. But the loop—the complete feedback path from sensor through logic to actuator and back—had no provision for ambiguous sensor states.

The loop is what matters. Not because the components aren't important, but because components only make sense in the context of the loop they're part of.

A binary sensor is perfect—unless environmental vibration causes intermittent connections. A safety interlock is necessary—unless it can't distinguish between unsafe conditions and sensor failures. A local control panel is reliable—unless diagnosing it requires knowledge and tools that aren't available on-site.

This is why you can't design automation by picking components and wiring them together. You have to design loops: understand what the system needs to observe, determine how it should respond to both normal and abnormal signals, and verify that the complete feedback path behaves as intended—including degraded sensor conditions.

Most automation problems are loop problems disguised as component problems.

Open-Loop Automation Is Optimism

Many automation failures are not caused by bugs. They are caused by loops that were never fully closed.

That dock control system had excellent safety interlocks—sensors, logic, actuators, all integrated. But it had no diagnostic loop. No way for the system to observe its own behavior and communicate what it was experiencing. No telemetry. No event logging. No remote visibility.

When the door sensor failed, the safety loop worked perfectly: detect ambiguous state, prevent operation, protect people and equipment. But there was no observability loop to help operators or technicians understand why.

This pattern appears everywhere:

- Systems that actuate but don't verify outcome

- Alarms that fire but have no authority to act

- Safety interlocks with no diagnostic telemetry

- Control panels that enforce logic but can't explain their state

- Analytics platforms that detect anomalies no one responds to

- Dashboards that inform no decisions

These are open-loop systems wearing the appearance of control. They work beautifully in steady state. They fail spectacularly during transitions—startups, shutdowns, disturbances, sensor degradation, and edge cases—because there's no feedback to communicate what's actually happening.

Open-loop automation is not engineering. It is optimism encoded in architecture diagrams.

The difference between "automated" and "automatic" matters. Automated means machines do the work. Automatic means the machines adjust themselves when things change. One is a tool. The other is a control system.

But there's a third category that's often forgotten: observable. A system can be automatic but opaque. It makes decisions, but you can't see why. It enforces rules, but you can't tell which rule is blocking you. It protects you from hazards, but also locks you out when a sensor hiccups—and offers no clue about which sensor or why.

Observability isn't optional. It's a feedback loop for humans trying to understand what the automated system is doing.

Remote Monitoring Is a Supervisory Layer

Remote monitoring is often sold as visibility. Visibility is useful, but visibility alone does not create control.

A remote system introduces latency, bandwidth constraints, loss of determinism, and unclear authority boundaries. At that point, you are no longer designing a control loop. You are designing a supervisory loop.

Supervisory control is valid—but only when its role is clearly defined.

Consider a hierarchical control structure: local control panels handle safety interlocks (milliseconds), site management systems coordinate operations (seconds to minutes), and cloud platforms aggregate diagnostics across facilities (minutes to hours). Each layer operates at its natural timescale. Authority is clear.

The dock safety system didn't need cloud control. The safety decisions—when to allow the door to open, whether the truck is properly restrained—must happen locally, instantly, deterministically. Those decisions can't wait for network round-trips or cloud processing.

But diagnostics? That's different. Diagnostics operate on a slower timescale. When a sensor starts behaving erratically, you don't need instant response. You need visibility—event logs, state histories, sensor signal quality metrics. Information that helps technicians diagnose problems without being on-site with specialized tools.

The missing piece wasn't faster control. It was slower observation.

Problems arise when these boundaries blur. When cloud systems try to make real-time control decisions. When local controllers wait for remote approval before acting. When "monitoring" systems are expected to prevent problems they can only observe after the fact.

Latency turns control into observation. But observation without control is still valuable—if the system is designed to provide it.

When Remote Observability Meets Local Control

Cloud platforms feel powerful because they are flexible, scalable, and abstracted from hardware. None of that exempts them from control theory.

Remote systems are best understood as high-latency, high-compute supervisory layers:

- Excellent for aggregation across multiple sites

- Excellent for diagnostics and trend analysis

- Excellent for coordination and maintenance planning

- Terrible for real-time safety decisions

This isn't a criticism of remote architecture. It's a description of its physics. Light only travels so fast. Networks have congestion. Cellular connections drop. These aren't implementation details to be optimized away—they're fundamental constraints that must be designed for.

The dock control panel could have had both: local, deterministic safety control (no network dependency, instant response, proven logic) plus remote diagnostic telemetry (event logs, sensor states, fault histories uploaded when connectivity is available).

This requires answering specific questions during design:

- What decisions must be local and deterministic?

- What information would help diagnose problems remotely?

- What happens when connectivity is unavailable?

- How long can diagnostics be buffered before critical information is lost?

- Who receives the diagnostic data and what do they do with it?

Most systems don't answer these questions explicitly. They treat remote connectivity as either essential (everything goes to the cloud) or unnecessary (everything stays local). The middle ground—local control with remote observability—requires more thought but solves real problems.

That four-hour diagnostic delay? With basic telemetry, it could have been four minutes. Not by making the cloud control the dock—but by making the dock tell the cloud what it was experiencing. Event timestamps showing the door sensor cycling 200 times per second. State machine logs showing repeated transitions between incompatible states. Signal quality metrics showing noise on the interlock circuit.

The technician could have arrived knowing exactly which sensor to check, maybe even with a replacement part already in hand.

Safety Is a Separate Loop

One of the earliest lessons in industrial control is also one of the most frequently forgotten: safety is not a feature of control—it is a separate control loop.

Safety systems assume the primary control loop can fail. They assume sensors can lie. They assume logic can be wrong. They assume humans can make poor decisions.

They exist precisely because automation works so well—and so relentlessly.

A control system optimizes for performance: throughput, efficiency, convenience. A safety system optimizes for survival: keeping things within boundaries that prevent damage, injury, or environmental harm.

These goals conflict. And when they're implemented in the same system, the conflict gets resolved through implicit tradeoffs that no one agreed to.

The dock control panel did this right: safety logic was primary. When the door sensor gave ambiguous signals, the system chose the safe response—lockout—over the convenient response—ignore the noise and proceed anyway.

But safety and observability are not the same thing. The system could safely refuse to operate while simultaneously logging why. It could maintain safety interlocks while transmitting diagnostic data. It could protect operators from hazards while giving technicians information to fix the hazard.

Instead, it protected operators but left technicians blind.

This is a common pattern: systems designed with robust safety logic but minimal diagnostic capability. The assumption is that if safety is handled, everything else is secondary. But "everything else" includes the ability to understand failures, plan maintenance, and avoid emergency service calls.

Safety loops must be independent: separate sensors, separate logic, separate authority to shut things down. But observability loops should be pervasive: instrument everything, log state changes, buffer diagnostics locally, transmit when possible.

These are not competing requirements. They're complementary.

Organizations Are Control Systems Too

This is where automation, technology, and management converge.

Organizations sense through metrics and reports. They decide through meetings and approvals. They actuate through people and processes. They respond with delay and distortion.

When feedback is slow, organizations oscillate—overcorrecting to problems that have already changed.

When authority is unclear, control saturates—multiple people trying to correct the same thing in incompatible ways.

When incentives are misaligned, the system drives itself into failure—optimizing locally while degrading globally.

These are not cultural problems. They are control problems.

That dock control panel? The decision to exclude remote diagnostics wasn't technical. The panel manufacturer offered telemetry as an option. The warehouse operator decided against it to save $200 per bay—$2,400 total across twelve bays.

That was a reasonable decision given available information: the system had worked reliably elsewhere, diagnostic issues seemed unlikely, and budget was constrained.

But no one in the decision-making loop had experienced the cost of a four-hour diagnostic delay. No one modeled the probability of sensor degradation over time. No one considered that the warehouse was remote enough that emergency service calls were expensive. The organizational feedback loop—the one that should learn from operational experience and adjust specifications—was open.

The result: $2,400 saved during installation, $800 spent on the first service call, plus lost productivity, plus the knowledge that eleven other bays could fail the same way with the same diagnostic blindness.

The technical system was local. The organizational learning system was also local—each facility made its own decisions based on its own experience, with no feedback loop to aggregate lessons learned across sites.

This pattern repeats: automation projects where procurement optimizes for initial cost without visibility into operational cost. Remote monitoring proposals rejected because "it's worked fine without it" right up until it doesn't. Diagnostic capabilities treated as nice-to-have features instead of essential observability loops.

The technical system can be well designed, but if the organizational system around it is open-loop, failures are inevitable.

The Pattern Repeats

This dock control failure is not unique. The specifics change—different equipment, different sensors, different facilities—but the pattern is constant.

Systems are designed with good control logic but minimal observability. Safety is prioritized (correctly) over diagnostics. Remote connectivity is seen as an unnecessary cost until the first time it would have saved multiples of that cost.

And the lesson gets learned locally, slowly, expensively—one emergency service call at a time.

This is where control theory meets organizational reality. The technical feedback loop (sensor → logic → actuator) works fine. The diagnostic feedback loop (system behavior → human understanding → maintenance action) is open. And the organizational learning loop (operational experience → design decisions → better specifications) barely exists.

Each loop matters. Each fails in predictable ways. And understanding one helps you recognize the others.

A Final Thought

Automation doesn't remove humans from systems. It changes where humans intervene—and how much information they have when they do.

The dock control panel didn't need humans removed from the safety loop. It needed humans with the right information at the right time: operators with clear panel feedback about system state, technicians with diagnostic telemetry about sensor health, managers with operational data about failure patterns across sites.

Well-designed systems respect that reality. They put fast control close to the process. They add observability where diagnosis matters. They keep safety separate from optimization. They ensure someone owns the complete loop—not just the components, not just the initial installation, but the long-term operational behavior.

Poorly designed systems hide these distinctions until something breaks.

Every automated system is a control system. Whether it behaves safely, stably, and predictably depends on whether its designers treated it like one.

The question is not whether you have automation. The question is whether you have control—and whether you can see what that control is doing when things go wrong.